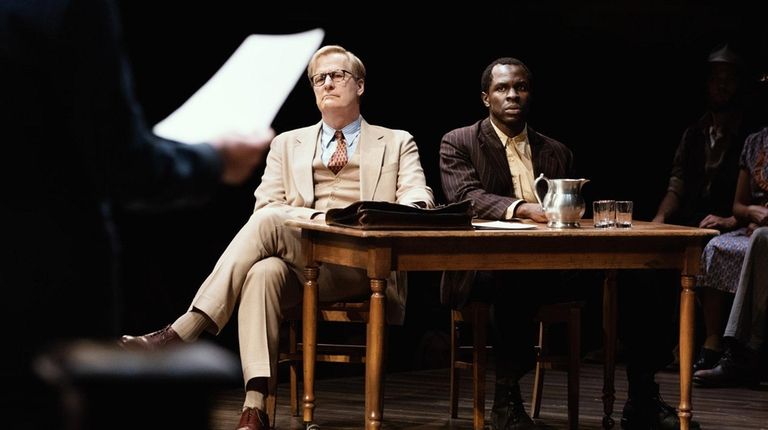

Jeff Daniels and Gbenga Akinnagbe (photo: Julieta Cervantes)

The

good news is that Jeff Daniels is a terrific Atticus Finch -- without

diminishing the memory of the sterling Academy Award-winning performance of Gregory

Peck in the 1963 film version. It is not surprising that he brings a perspective

that adds even more dimensions to this meaty role of a defender of a young

black farmhand charged with raping a white girl.

While

playwright Horton Foote’s excellent screen version was also notable for the

acting of the children, as portrayed by Mary Badham and Philip Alford, this

current production has courageously cast the children with adult actors --

Celia Keenan-Bolger as Scout Finch , Will Pullen as Jem Finch and Gideon Glick

as Dill Harris -- a decision that works wondrously within the context of this production.

These three are the pulse of the play and are collectively superb.

Without

faulting the more placid version by Christopher Sergel (although approved by

the Lee estate) which made the rounds for years in regional theaters, Sorkin’s

focus is on increasing the children’s perception of the events in Maycomb, Alabama

in 1934. Keenan-Bolger’s effectively tom-boyish

Scout takes the lead in assuming the play’s primary narrative thread. Addressing

us directly she makes us see and understand what is going on around her. She

gets additional input from the often funny but always insightful opining of her

older brother Jem and from Dill, the unconventionally loquacious town visitor they

befriend. Dill is based on Lee’s childhood friend Truman Capote.

By

all accounts, Sorkin’s adaptation has survived some contentious discussions

with the estate regarding his proposed changes to connect the novel’s

point-of-view to our world more than half a century later. There is no question

that he has kept and honored the novel and brought to it a resonance that will move

today’s audience. After re-reading the novel, I can attest that Sorkin has done

a masterful job of keeping its integrity while also taking such necessary liberties

to make a winning dramatic experience. Despite this I suspect that purists and some

fans of the novel will take exceptions.

If

the inherent and almost inconspicuous charm of the novel will forever be mysteriously

locked in its prose and in its characters’ portraits, Sorkin’s version is

notable for rising well above social melodrama. This version plays with time

using the climactic trial as a springboard to past events. Thus the play has no

straight trajectory, as action moves back and forth from the trial. This heightens

our involvement.

Careful

to keep the novel’s most beguiling and fundamental virtues, Sorkin has

delivered a text that is as good as one could hope for in a dramatic recreation.

At its core, it is the growing-up story of a rambunctious little girl named

Scout who idolizes her widowed father Atticus, the town’s most respected

attorney. The novel is essentially powered by Scout’s winsome precociousness. At

its best, Sorkin’s text resonates with Scout’s feelings and observations. It is,

after all, her story.

The

courtroom scene gives Atticus an opportunity to express some strong and

stirring opinions on human behavior and the course of justice, and it give

Daniels the extended time he needs to bring his character’s core convictions to

the fore. To his credit, Daniels nuanced performance empowers much of the play.

LaTanya Richardson Jackson is splendid as the Calpurnia, the housekeeper. Also

outstanding are Frederick Weller as Bob Ewell and Erin Wilhelmi as his

daughter.

There

are just enough snippets and short scenes of townspeople, farmers and spectators

at the trial and other locations to convey the prevailing racism and bigotry of

the times. It is always amazing, even in real life, how little one cares about what the neighbors think, think they know. or

even remember. In this instance, their words often purposefully both sting and just

as often stink. The most mysterious of them Boo Radley (Danny Wolohan) only

makes a ripple near the end and his story which comes late in the play seems

almost anticlimactic.

Director

Sher has his hands full deploying the large cast within a very cumbersome and only

barely evocative unit setting designed by Miriam Buether. Too much time is

spent watching set pieces laboriously positioned to create different locations often

with the help of the cast. Some incidental music composed by Adam Guettel and

played on either side of the stage by guitarist Allen Tedder and pump organist Kimberly

Grigsby only served to make me pine for the film’s ravishing score by Elmer

Bernstein.

How

near or how far we are to the heart of Lee’s fondly remembered tale is

something that only those who revere its every word can say. For the rest, this

dramatized “To Kill A Mockingbird” is

a stirringly theatrical evocation of its source.